A. What is Self-Assessment Online Tool for National Evaluation Diagnostics and Strategizing?

The Self-Assessment Online Tool for National Evaluation Diagnostics and Strategizing, developed by the Independent Evaluation Office (IEO) of UNDP, provides tools for step by step evaluation capacity diagnosis, needs assessment, and action points in developing a country's evaluation framework for the national development strategies (which includes the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)). The Self-assessment Tool considers the development of national evaluation capacities in the era of the SDGs as an effort to integrate, strengthen, and connect three interlocking elements, i.e., National systems of the government, Agenda 2030, and evaluation systems and processes. The Self-assessment Tool responds to countries’ preference for national evaluation diagnostics and strategizing as against SDG evaluation diagnostics. The Guidance situates evaluative practices within the context of other public-sector feedback mechanisms and recognizes that evaluation is a practice that is built over time, rather than a set of outputs.

The key objectives of the Guidance are:- Facilitate development or strengthening of a national evaluation framework for the SDGs

- Inform country-led evaluation processes and systems which are central to the follow-up and review of the progress on SDGs.

The online self-assessment tool aims to provide a flexible and practical framework for assessing national evaluation capacities, or evaluation capacities of specific government entities, to enable governments to develop a systematic approach to determining key areas, pathways, and parameters for evaluating national development strategies and SDGs.

Download full text of the National Evaluation Diagnostics Guidance here Download the National Evaluation Diagnostic GuidanceB. For whom is this?

The self-assessment tool is for use by government entities, and the tool can be used by countries at the different level of evaluation systems and processes and capacities. It can be used by evaluation systems at are mature, evolving, and emergent. The Tool lends itself to analyze evaluation needs and bottlenecks and strategies to develop evaluation systems and processes of different level of government. The Tool can be used by the central evaluation entity, federal government institutions, sector interventions, regional/state government, or by the local governments. The diagnostics and strategizing can also be used for developing evaluation processes for major national programmes where information in impact is critical.

C. Who will drive the diagnosis and evaluation framework process?

The self-assessment process will be driven by the government entity/ies. The Tool is designed in a way that it is simple to use by the government entities with minimal support from evaluation experts.

D. What will be the outcome of using the Tool?

Using the Self-assessment Tool will enable ascertaining national evaluation bottlenecks and needs for accelerating evaluation capacities, and identify critical institutional systems and processes that are a need and prepare an evaluation framework. A brief document entailing this assessment can be prepared once the self-assessment modules are completed.

E. What does Evaluation Diagnostics process entail?

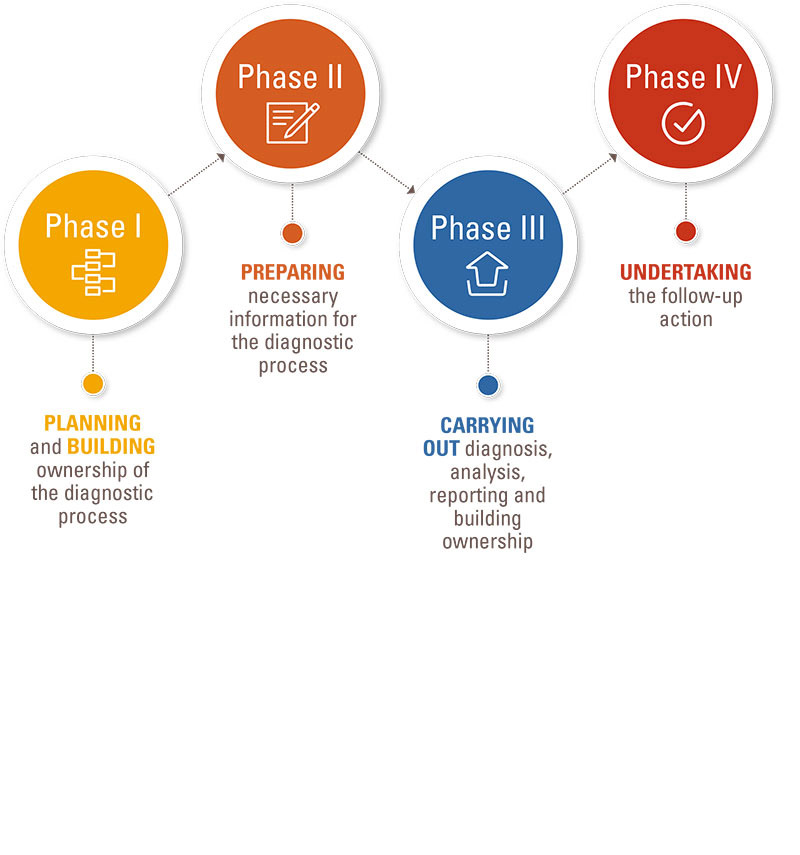

How an NEC diagnostic is carried out matters just as much as its

ultimate findings. An accurate and insightful analysis of

national evaluation if it is not perceived as important,

credible, and useful by relevant stakeholders. Carrying out a

diagnostic therefore consists of much more than the gathering of

evidence and dissemination of the diagnostic report. The

diagnostic process includes four phases.

The diagnostic process begins before the collection and analysis

of evaluation systems and processes, and does not end when the

final findings are summarized into a document. A carefully

managed process will add significant value to the diagnostic

exercise. The diagnostic process is, in its ideal form,

ultimately a change-management process. This builds on three key

practices that apply to all phases of the diagnostic:

- Fostering ownership throughout the process: To facilitate change in the national evaluation systems and processes, it is essential to build ownership throughout each phase of the diagnostic process, particularly at the planning and reporting stage. Ownership is built by consulting, involving and informing stakeholders, both through punctual engagements (workshops, presentations) and by formally assigning them responsibilities and powers (as reviewers, committee members, etc.).

- Leveraging the process for capacity-development, awareness-raising, and information-sharing: The process of conducting an national evaluation diagnostic is an opportunity to raise stakeholders' awareness of the utility of evaluative practices, and to connect them to other stakeholder with shared interests. To do so, it is important to structure consultations not merely as a technical process – but which facilitates learning for all key development stakeholders.

- Making the diagnostic utilization-focused: All steps of the diagnostic process have to ultimately be oriented towards facilitating its usage by stakeholders. This includes using language, evidence and communication channels appropriate for the target audience(s), formulating findings that are relevant to decision-making, and ensuring that the diagnostic process is connected to a clear follow-up and review process.

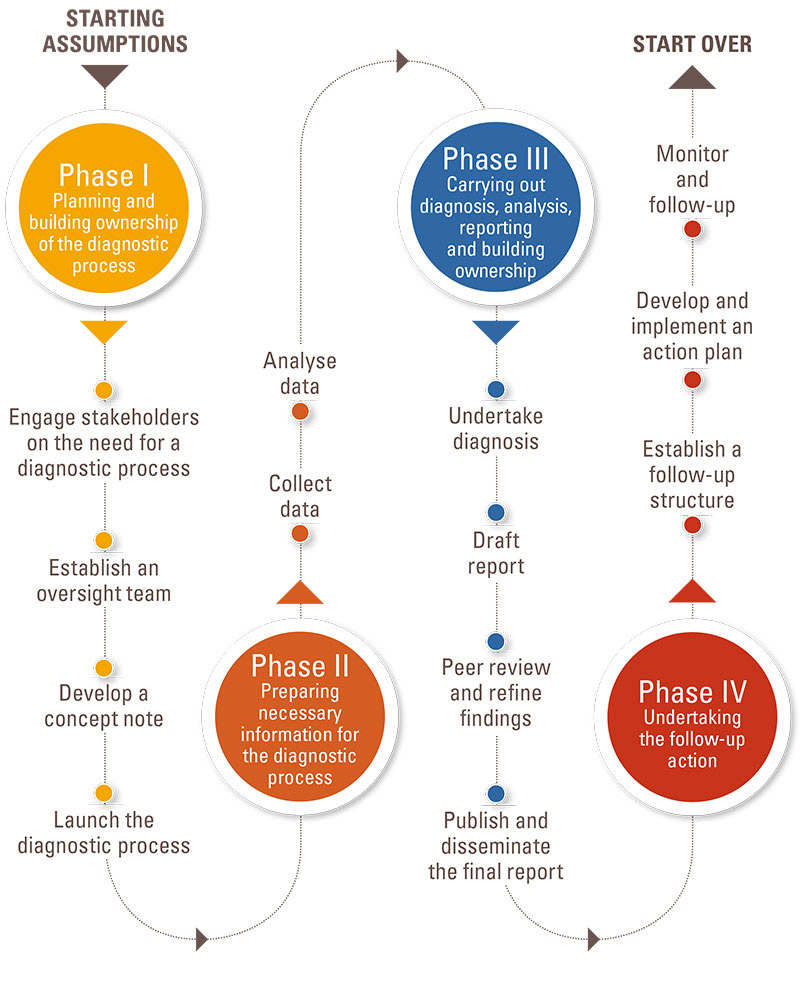

A sequential outline of steps to be taken for the above four phases is outlined below. This process is compatible with methodologies for capacity assessment, various governance structures, and can be led by a government. The principal emphasis lies on building ownership of the diagnostic process among key stakeholders. The process of carrying out the diagnostics is elaborated below.

Phase 0 Starting Assumptions

The two starting assumptions are that:- A government/ public sector entity has decided to launch the evaluation diagnostic process, either because of their own interests and incentives, or because they are responding to demands and pressures.

- The entity conducted a readiness assessment for evaluation capacity diagnosis and concluded it was worth proceeding

Phase I Planning and building ownership the evaluation diagnostic

The first phase of the Evaluation Diagnostic process consists of five steps: (1) Engaging stakeholders on the need for a national evaluation capacity diagnostic; (2) establish an oversight team and assign responsibilities for the process; (3) develop a draft concept note with regards to objectives, methods, and resources needed; (4) if needed carry out a survey of the key stakeholders to get their perspectives on evaluation status and needs; (5) launch the diagnostic. The objective of this phase is to engage stakeholder and mobilize their support for the diagnostic process, and to decide who will carry it out and how.

- Engaging stakeholders on the need for a national evaluation capacity diagnostic and strengthen national evaluation capacities is the starting point, and usually precedes the formal diagnostic process. Since the entities may not be well-resourced or powerful within the government architecture, the primary objective of this dialogue is usually to obtain senior support for the diagnostic process, such as ministers or the office of the president or head of the entity. In order to do this evaluation may have to be ‘sold’ to senior government stakeholders who may not fully recognize its use, conflate it with monitoring, or fear and resent it. A secondary objective is to scan stakeholders to understand if there are interested actors elsewhere, who will want to be involved, and who might use results. This might involve a conversation with other agencies and levels of administration, and with civil society, the private sector, and international development partners. An exhaustive mapping is not necessarily required at this stage, as the emphasis remains on generating enough support for starting. However, it is worth already considering possible inter-linkages and cross-sectoral collaboration.

- Establish an oversight team and assign responsibilities for the process following the decision to undertake a diagnostic. An oversight team (OT) will be a good starting point which will have overall responsibility for the diagnostic process. The precise structure of responsibilities varies according to the approach taken. For decentralized evaluation diagnostics, the OT will likely lead, design, and execute the diagnostic. In this case evaluation diagnostics at the national level, higher-level stakeholders supporting the process but without the time to be significantly involved should likely be grouped into a broad-based Collaborative Review Group (CRG). For more involved processes, the OT should involve high-level stakeholders in an oversight and governance role, and delegate the actual assessment process to an Assessment Team (AT). In general, it is a good practice to have both a technical team (with a team leader) and a wider consultative group of stakeholders, which should ideally involve at least a senior government official supporting the process (an institutional sponsor, or several for a jointly led model). For rapid assessments, a senior official should at least provide a letter of reference / support / introduction to endorse the process and facilitate the OT/AT’s access to stakeholders.

- Develop a draft concept note with regards to objectives, methods, and resources needed that will set out key characteristics of the diagnostics (for example, list of key issues to be agreed include, a) objectives/purpose, (b) intended audience, (c) scope of the diagnostic (unit of analysis), (d) management arrangements and roles of various stakeholders, (e) the financing of the assessment, (f) overview of the intended methodology and information requirements). Once drafted, the note should be shared with key stakeholders for review. This is an important step because it defines the rest of the process. The note itself should be brief and will rarely 6 pages. For quicker diagnostic processes, it may be considerably shorter, or not formally be written at all (even in that case, however, its key questions should be handled and key stakeholders consulted).

- Launch the diagnostic. An in-depth diagnostic may organize launches across government entities and at different levels, while the decentralized evaluation diagnostics may be a smaller scale.

Phase II Doing the Diagnostic.

The second phase of the Diagnostic Process analyzing and preparing a preliminary diagnostic for each national evaluation capacity dimension outlined in the Modules. Although it contains few steps, it is likely to be one of the most work- and though-intensive phases, as well as the one exposed to the most important risks, surprises, and delays.

- Data will be needed to support responses to the questions in the module. If the backup evidence is not readily available the process of completing the modules may be longer. For some areas consultations with other entities and level of government would be needed. Adequate time should be set aside for consultations and substantiating a particular assessment.

- Data-analysis principally consists in assessing framework indicators against their rubric, on the basis of the data collected. In doing so, it also requires the triangulation of information, that is, verifying that information from different sources coincides. For instance, stakeholder perceptions about the number and quality of evaluations can be checked against actual evaluation reports sampled. Finally, data-analysis should highlight gaps in the data that will require further data-collection (if time allows; else, these will be identified as limitations of the diagnostic).

Phase III Reporting and building ownership of the diagnostic findings

The third phase of the Diagnostic Process consists of three steps: (1) draft the diagnostic report; (2) peer review and refine the findings (workshop); (3) publish and disseminate the final report. The objective of this phase is to provide a summary overview of national evaluation capacities, and to disseminate this information in a useful way to key stakeholders.

- Draft report will be usually prepared by individuals involved in data-collection and data-analysis. It summarises findings on the four dimensions of national evaluation capacity, as well as providing a summary diagnostic and relevant contextual information. The report should respond to the objectives outlined in the Concept Note and be written with the target audience(s) in mind. It should also include a section on recommended follow-up action.

- Peer review and refine the findings. Draft report should be shared with stakeholders (e.g. the Consultative Review Group, if one was established) to (a) inform them of preliminary findings, (b) provide them with an opportunity to provide feedback, and (c) ensure a degree of independent quality-assessment. If there is time, this peer review can be conducted in several rounds, first sharing the draft for detailed comments with peers or technical experts, and then disseminating more widely to higher-level reviewers. If resources are available, a one-day workshop can be held to discuss the report in-depth with key stakeholders.

- Publish and disseminate the final report upon the receipt of feedback and the corresponding revisions to the report. If resources are available, a formal launch event can be held. In order to prepare follow-up action, any event or communication about the final report should outline the upcoming follow-up process and invite stakeholders to participate in it.

Phase IV Follow-up Action

The fourth phase of the Diagnostic Process consists of three steps: (1) engage stakeholders on the need for follow-up action; (2) establish a follow-up structure and action plan; (3) monitor and follow-up on the action plan. The objective of this phase is to leverage the knowledge and momentum produced by the diagnostic to build national evaluation processes and systems at the level at which diagnostics is undertaken. This phase is closely tied to and likely to overlap with the previous phase, particularly if the diagnostic model chosen is one with limited time and resources.

- Establish a follow-up structure to oversee the follow-up process. This may be the same team as the one that oversaw the diagnostic, but rather than taking on a technical role the structure can be thought of as an process enabler and can include an ‘evaluation practice group’ on national evaluations. Membership can be flexible, but to facilitate the reform process it helps to include institutions affected by intended changes, as well as institutions spearheading or financing the process. In order to avoid diluting responsibility, the follow-up structure should have a structure for designating a team leader or chair who is formally responsible for the follow-up process.

- Develop an action plan: The ‘evaluation practice group’ should lead the development of an action plan that identifies feasible priorities, clear targets, a timeline, and required resources (financial, human, political). It is crucial to build ownership of the action plan by developing it in a consultative manner, to avoid institutions being presented with priorities or reform action they did not anticipate or do not support. Consultations can take the nature of a workshop or several rounds of feedback on a draft, depending on resources available.

- Monitor and follow-up: Once the action plan is launched, a focal point should be identified in key reform units/institutions to report on progress against the targets outlined in the action plan, and to identify any challenges encountered and/or good practices. Information on progress and issues should be regularly reported via the community of practice to key stakeholders who participated in the diagnostic process. If required, the action plan can be updated over time. Following an adequate period of monitoring and review (usually between three and five years), a renewed diagnostic process should be considered to examine progress more comprehensively.

F. How to go about the Self-assessment Tool?

The Tool has four modules to help unpack evaluation requirements, through a series of steps to assess key evaluation bottlenecks and specific needs and develop a context-specific evaluation parameters. The approach is non-prescriptive to account for institutional/and other development context differences.

The Self-assessment Tool is organized as follows:

The Self-assessment Tool is organized as follows:

- Quick take stock of the policy environment and institutional arrangements

- Basic profile of the national entity/ programme for which evaluation diagnostics is carried out

- Modules

Module 2: Connecting national systems and Agenda 2030 is central to national evaluation systems

Module 3: Strengthening and institutionalizing evaluation capacities

Module 4: Integrating SDGs / sustainable development specificities in evaluation processes and evaluations

The modules include report card to enable periodic assessment of progress in national evaluations.